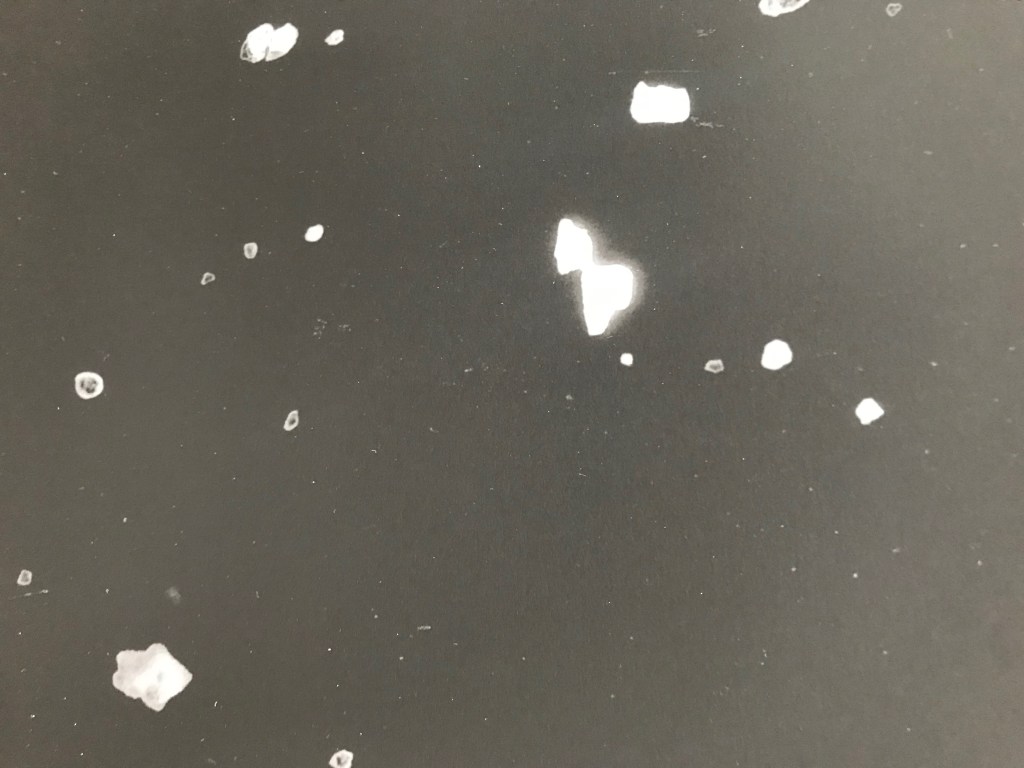

My central point of fascination was about ownership and authorship and the taking over of another artist’s artworks or practice. Listening to the critical responses, I can see that many people felt more engaged by the cracked earth discs on my studio bench than by the finished Kintsugi piece.

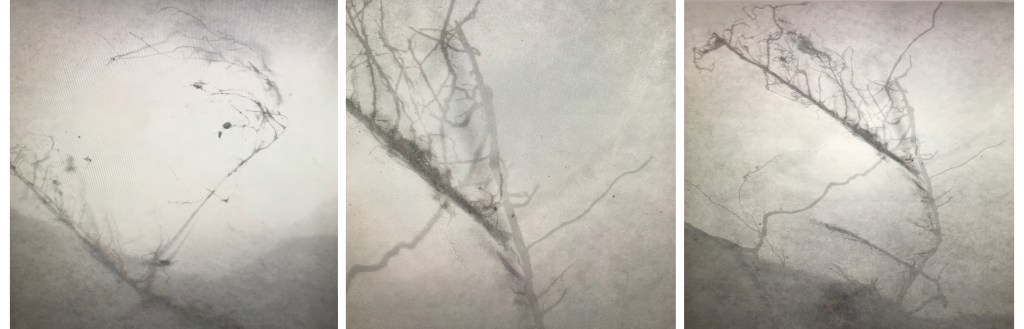

The constraints of Covid lockdown meant that all artworks were necessarily displayed via digital photography (or video) online. I presented my kintsugi piece [Alchemy I; unsolicited collaboration, 2020] as being a physical object mounted upon a distressed grey wall (that therefore highlights the natural forces of entropy inherent in all things and removes the piece from the stark white gallery context).

Although, when viewed online, it would have remained identical, on reflection I feel that the piece operates more successfully as a photographic work than as a displayed physical object, in both aesthetic and conceptual terms; as it is the idea of the piece rather than the piece itself which is the more important consideration. To further the ideas of ownership and authorship, it would be interesting to commission a professional photographer to take the image that is ultimately displayed as the finished piece. By involving a third artist in a third medium, with each of us in collaboration overlaying each other’s art practices, I think the resultant artwork is made stronger.

I think Alchemy I; unsolicited collaboration was very lineal and literal in its translation from idea to tangible object, and as such suffers from leaving little room to breathe; the art piece and the ideas within it are closed down too quickly. I value and enjoy the interlaced layers of meaning I find behind and within the piece but perhaps viewers need some room to formulate their own associations and prefer a tad more ambiguity. At present I find it difficult to conceive of a way to make artworks addressing the theme of taking over another artist’s practice in a more abstracted way. But I would like to come back to this theme in a few years when my understanding of my own art practice has grown and matured.

Feedback from the faculty, cohort and guests:

People responded well to the idea of the earth being borrowed and it potentially being returned to the roots of where it was borrowed from, in its own form of ‘unsolicited collaboration’. There was also a response to the image of the cracks in the earth and the golden roots as having a healing association; perhaps even relating to the self and the therapeutic mending of perceived imperfections.

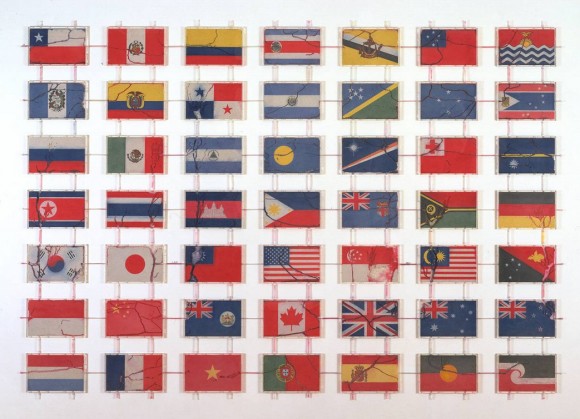

Questions were asked about the types of object that traditionally might get mended; which is an interesting consideration. The material context of gold was remarked on and it being both a mineral and a commodity. It being the literal standard to which currencies are measured against. It therefore signifies a particular kind of security.

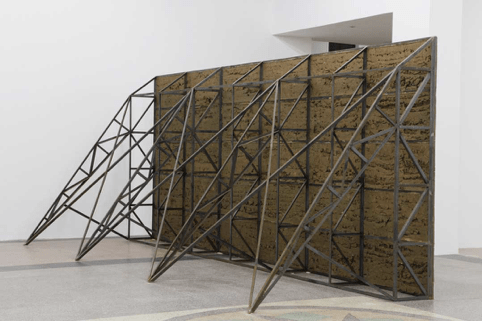

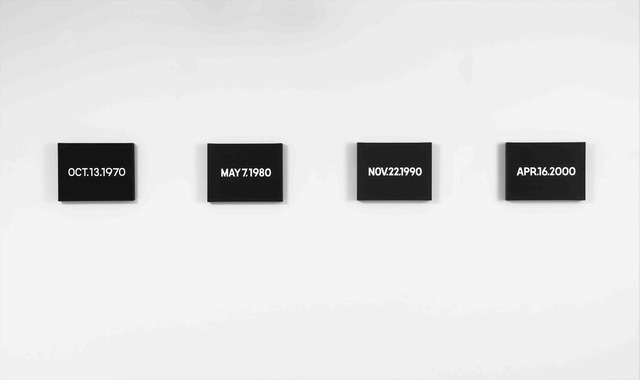

Arte Povera (and its utilisation of limited resources) was mentioned as too Ai Weiwei’s artwork:

His radical act being part performance, part political commentary on cultural worth, symbolic power and historical value systems.

The idea of fissures resembling thread-like root systems (as seen in my studio in their early stages) seems to be fertile territory for further exploration.

We discussed containment: mud banks, wood (as seen in the background of one of my photos) often used as a structural containment device). Also we talked about relation to site. That an artwork need not necessarily take place within a gallery context. It might exist in the community or within the same place as the material was originally sourced from.

An idea was suggested that I might consider ‘guerilla kintsugi pothole filling’ (mending broken urban pathways in the community with gold). This has however been done:

The circle was thought to be representative of Mother Earth and of the Earth being under enormous stress and the action of mending with gold, a healing process.

Some viewers found the aspect of having both the breaking and mending within the same piece to be a bit confusing; a complication; an anomaly.

Another artwork was mentioned in relation to the mark of one author overwriting another: Rauschenberg’s erased de Kooning drawing (1953). I watched a (sadly uncredited) interesting interview with Rauschenberg about this piece. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tpCWh3IFtDQ). Apparently it was really difficult to erase and took two months to do so. He described it as poetry, not vandalism.

I found it very interesting to note that as he was stealing up the courage to ask de Kooning for an artwork of his to erase, he was prepared for his own idea to ‘fail’ and maybe the failure itself would be the artwork. Maybe the artwork would be about asking de Kooning if he could erase a picture, and that would be okay. Maybe the process itself is the artwork instead of a finished displayed object.

Talking things over with my supervisors it is agreed that I should experiment with not knowing; experimenting with no up-front rationale for the series of choices made. To put concepts to one side and explore.