Group Crit (including Abbie, Claudia, Megan, Abigayle, Te Ara, Salle and Victoria):

After an initial cold read, here are some notes of the comments made about the artworks:

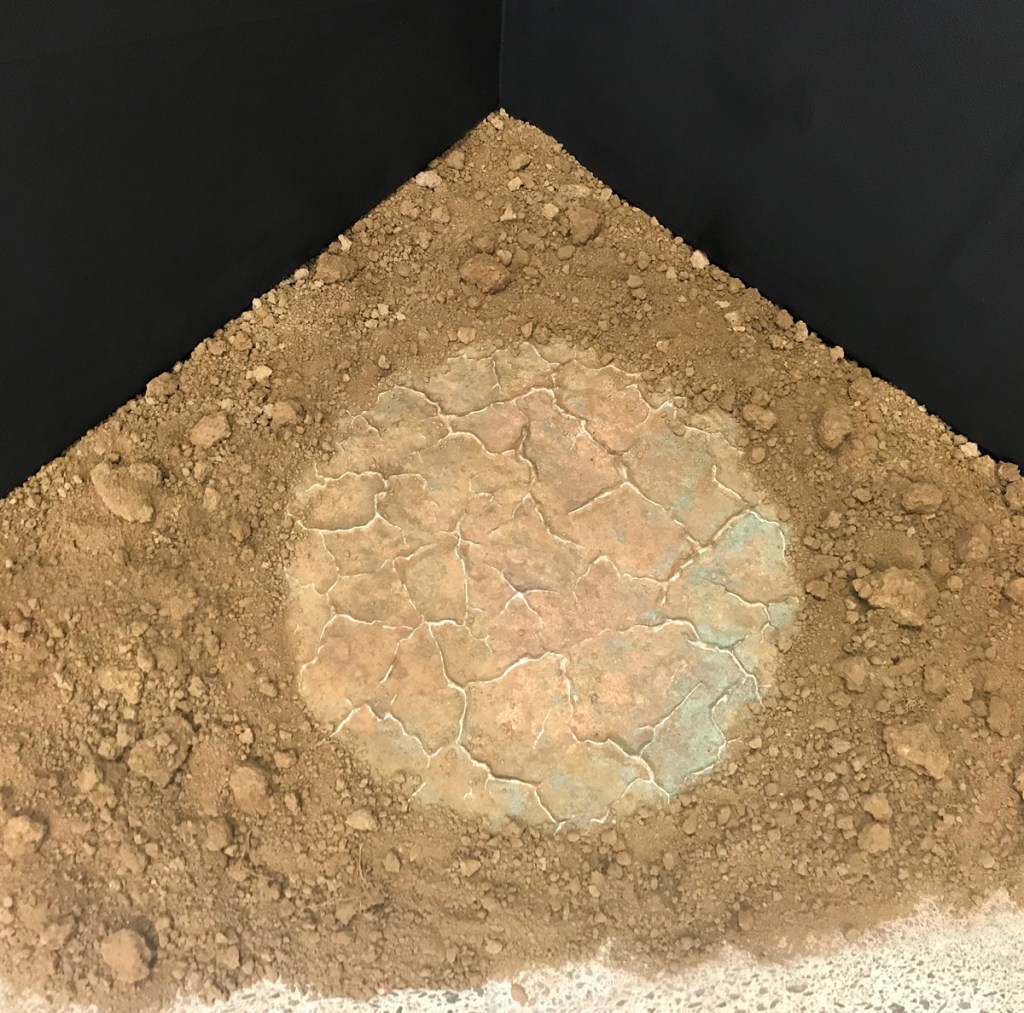

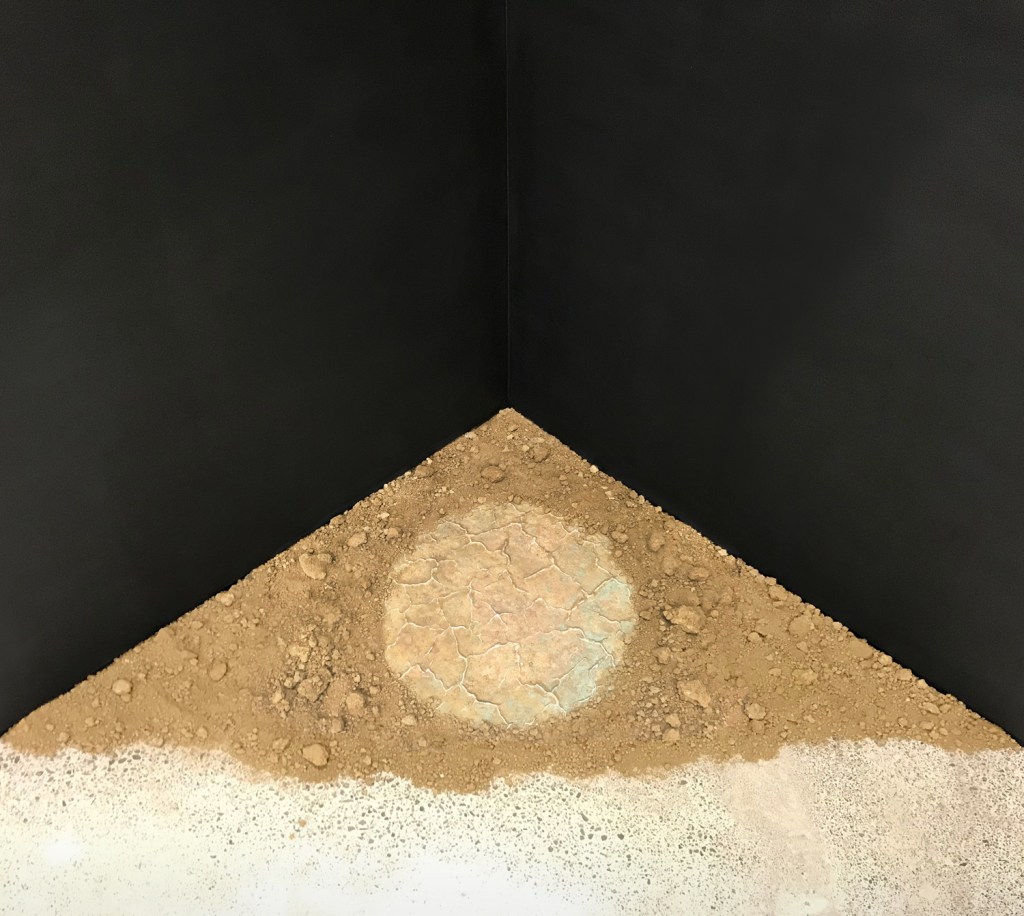

- Circle used as containment

- Reference to Rachel Whiteread

- Like a petri dish; a specimen feel but scaled up

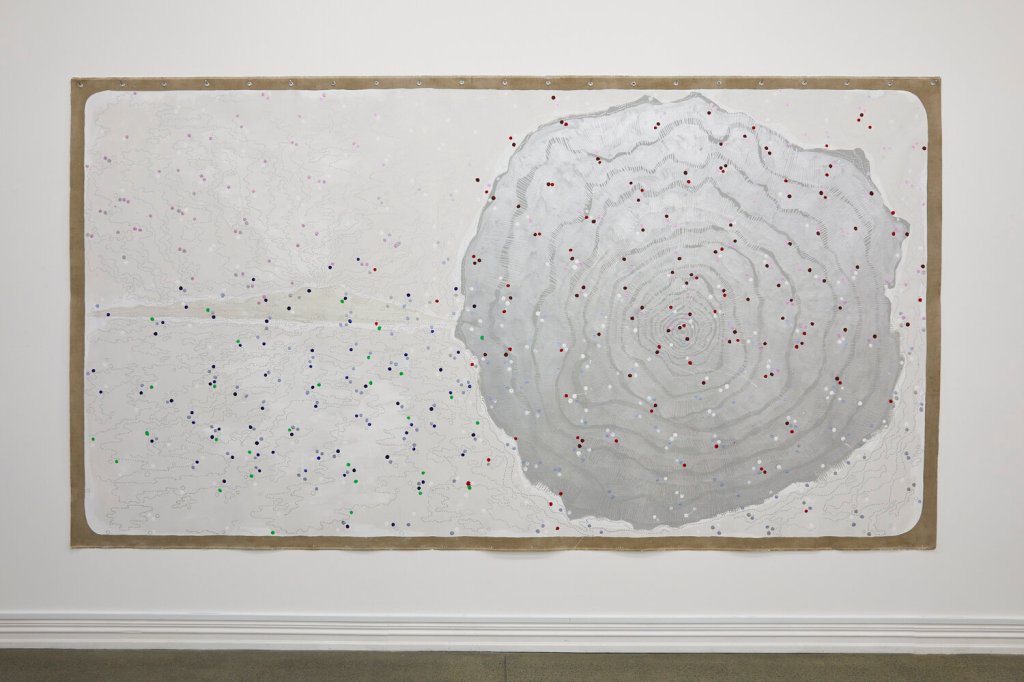

- The mud disc is lost

- Reparation Aesthetics by Susan Best might be worth looking at

- Have you read any Heidegger? (The Origin of the Work of Art )

- Earth – brute matter of the planet

- Opposites happening at once

- Do you intend to let go of something here – past work?

- Presence/absence – a bit glib. It doesn’t do it justice

- The circle as a formal device

- What are you saying?

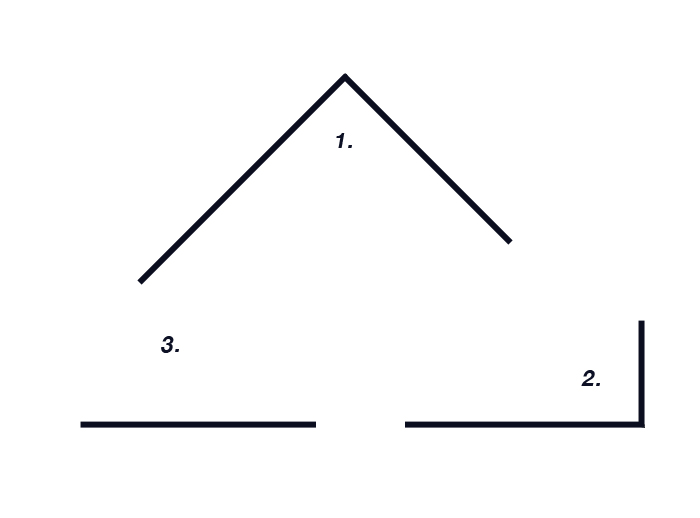

- Presence and absence is all within work 2 (the earth painting and white laser cut)

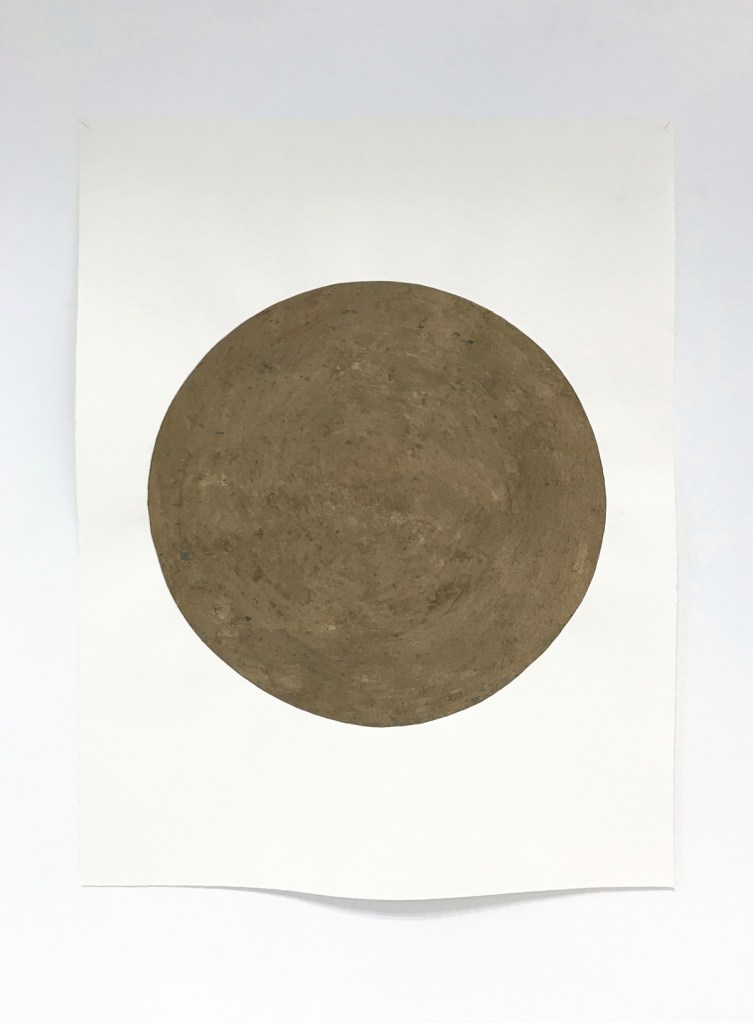

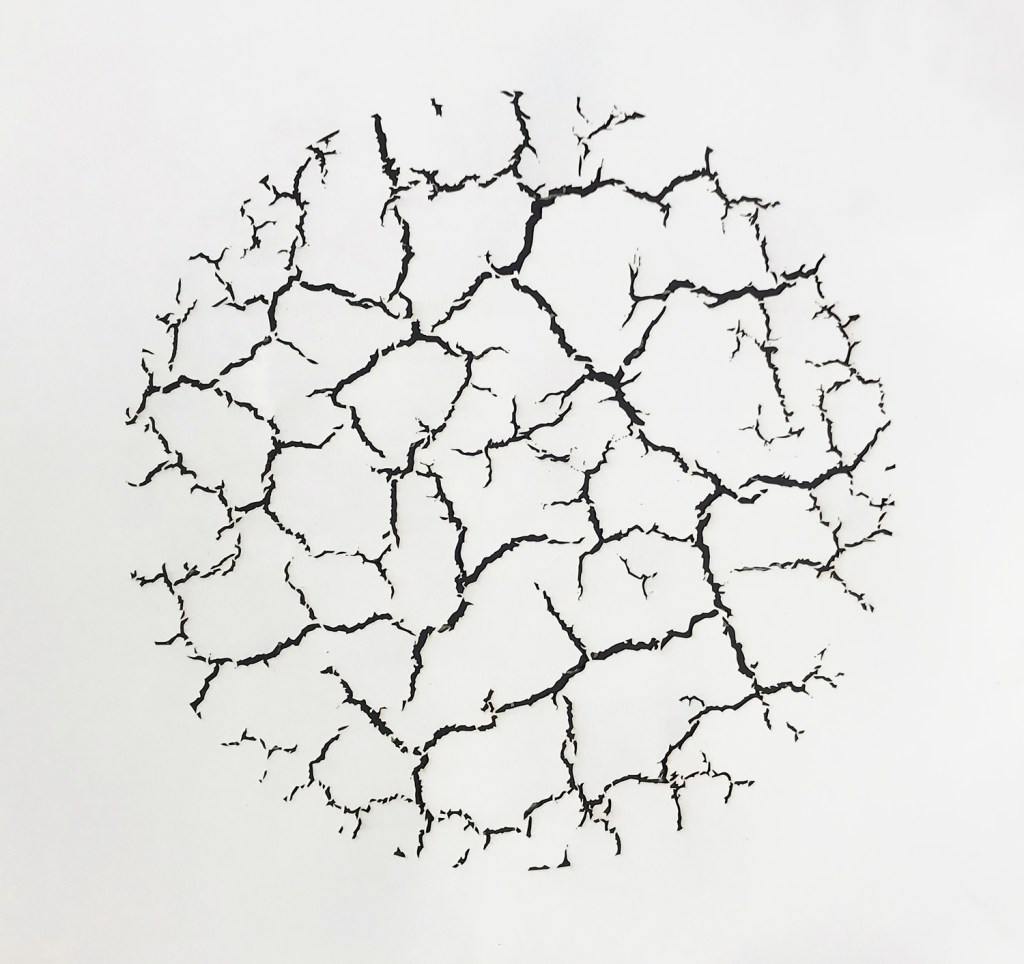

- The laser cut works are good. Just displaying the 3 circles on paper would have been really strong

- Practice based research (as opposed to research based practice) is what is happening. And through it you have come across something

- Suggestion to look at the works of Alan Fletcher (MFA graduate)

- Victoria is reminded of the work of Simryn Gill:

Cast in bronze from a crack in the ground formed during a long drought. The bronze makes permanent that which ordinarily is mutable and transient. It records but a moment in the cycle as the original earth rupture will continually change over time; through alternating wet and dry seasons, the crack filling with water and dirt then subsequently desiccating once again.

From the Examining Panel (Yolunda, Victoria, Balamohan, Dane and Elle):

- Balamohan suggests that the poetry should reside within the artwork rather than within the artist statement. Be careful not to over repeat a motif.

- The work is more interesting when I speak of the processes used to make the works

- Elle asks about the seriality timeline-wise

- Further trialing of object and image placement might benefit the installation

- Building a meaningful awareness of context (primarily contemporary) is important.

- Questions asked:

What were the decisions around the installation layout? What lead you to make this work? How do you see the works speaking to each other? Where to from here?

Critical reflections – a discussion with Dane and Elle:

- The soil was not needed on either of the ground works. It’s like an over-explanation of themes. I need to have more confidence in the audience to make the associations for themselves. My initial thought, in the placement of soil, was to juxtapose the free-flowing natural material alongside the dense, constrained and no longer potentially life-supporting bronze disc replication of it. I had worried that without the soil, the disc – a potentially ‘awkward’ object, might be too overbearing if left to stand on its own.

- The earth circle painting and floor laser cut tucked in a corner could have benefitted from not being so tucked away. Trying the artworks in different configurations ands spaces to see how they work with each other would be of value.

- Continuing working with paper would be a positive journey forwards. It might be useful to question the choice of the weight or type of paper used.

My Reflections:

This work stemmed from an exploratory stance of focusing on materiality and process, leaving all preconceived associations of meaning and intention behind. This is completely counter to my usual way of working. Though informative, I found this method to be not the most beneficial mode of art making with regards to my particular practice; as although encouraging me to fully encounter the medium at hand it ultimately leaves me with an object I have difficulty in comprehending. Making inexplicable artefacts is not my fascination point. My joy and drive comes from collating, creating and finding meaning and associations between objects. This exercise has helped me to understand and acknowledge that.