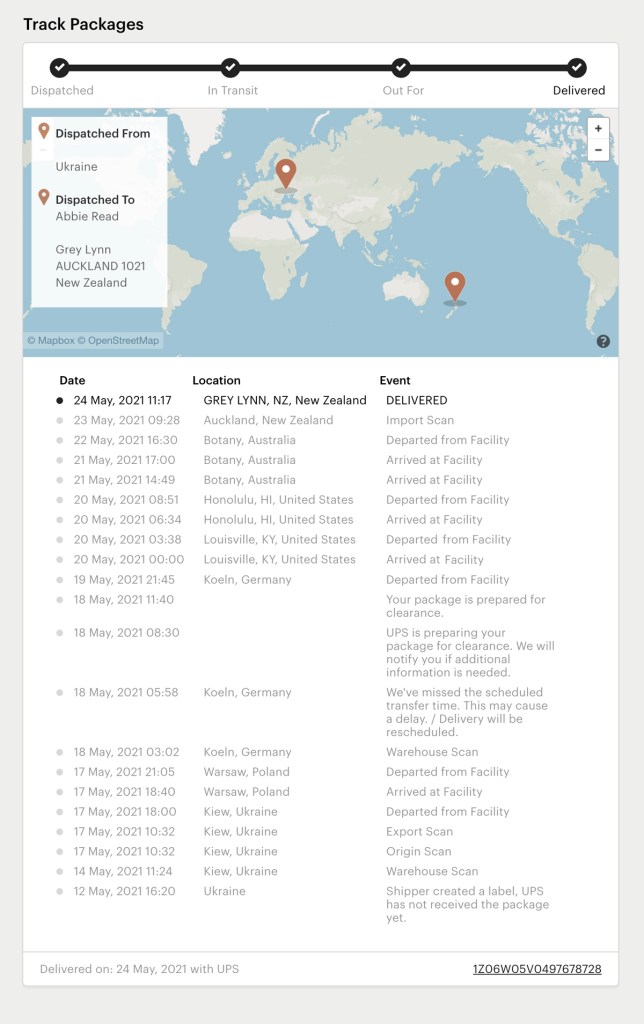

wooden panel from the grand staircase, Pah Homestead, Auckland

Working mostly with materials garnered from the natural environment: with wood, with clay, with bone, I seek to explore their innate connotations to the New Zealand landscape and its composite stories and histories. My curiosity lies in the pairings of objects, their relationship to site and the dialogues held within. I see my role as a collector, collator and assembler; part archivist, part storyteller.

I am drawn to the use of readymades as raw material; specifically, at present, wooden artefacts relating to colonial furniture. In this there is an acknowledgement of the lineage of nameless artisans who first created these objects; a usurping of their knowledge and skills, a deposing of their ‘authorship’; a new ‘colonisation’ as it were. I also consider timber as a living readymade, as both commodity and archive, biographical traces chronicled within its rings and contours.

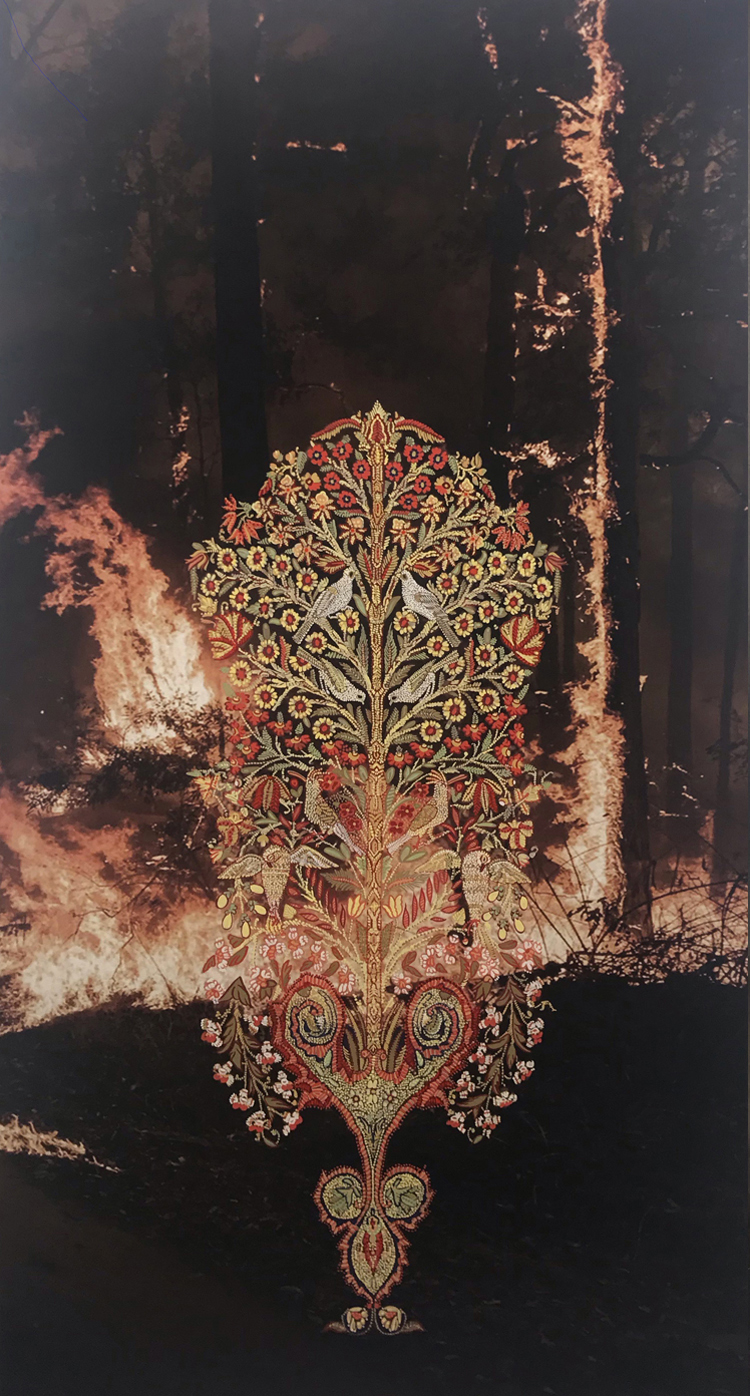

I am interested in the relationships between native and non-native flora, of the exchanges that take place and the losses induced. I am interested by the canonical systems that designate certain species as ‘weed’ and how these classifications evolve and dissolve throughout differing timelines and geographies. I am interested in how migration through time and physical space seemingly alters intrinsic worth and perceived usefulness and of how this ratio of value and utility is a complex balance.

My practice currently involves the process of charring timber. I delight in both the aesthetics and symbolic pertinence of the action in its many iterations. The use of traditional Japanese yakisugi techniques, itself an act of acculturation, focuses on the dualities of preservation and decay; a seemingly destructive gesture, conversely promoting the conservation of the wood. Later artworks have focused on the burning process as an eradication, an enforced entropic happening, invoking a sense of loss and melancholy. At present, the charring relates more to homogenisation; a blurring of the differentiation between materials or geographical and cultural origins. It references the histories of landscape, of wood, of furniture. It implicates the obliteration of the old and the overwriting with the new; the cyclical exchange and transposition of one culture by another; the evolutions that take place within the land, within species, within communities.