DEMO 3.0 215 Karangahape Road, Auckland

Lively collisions 22 October – 23 October 2020

Dan Arps, Gitanjali Bhatt, Fiona Cable, Samantha Cheng, Stella Corkery, Brunelle Dias, Claudia Dunes, Matt Ellwood, Celine Frampton, Louise Kenn, Giulio Laura, Wendy Lawson, Tanya Martusheff, Dane Mitchell, Abbie Read, Glen Snow, Amy Unkovich

LIVELY COLLISIONS

In October 2017 Scientists detected a mysterious object hurtling past our solar system. The object 11/2017 U1 was given the name ‘Oumuamua, a Hawaiian term for scout or “messenger that reaches out from the distant past.” Analysis showed its orbit is almost impossible to achieve from within our solar system, therefore its origin is interstellar. ‘Oumuamua is the first space rock identified as forming around another star, according to researchers it could be one of 10,000 lurking undetected in our cosmic neighbourhood.

It was noted that after passing the sun, ‘Oumuamua suddenly sped up, could it have been pushed by the sunlight striking it, like a deliberately designed solar sail? Some speculated that ‘Oumuamua is a light sail, floating in interstellar space as debris from an advanced technological equipment. In early December 2017, astronomers on an alien-hunting project known as Breakthrough Listen used the huge Green Bank telescope in West Virginia to monitor ‘Oumuamua for radio signals in case it happened to be a passing spacecraft, and not an interstellar asteroid after all. To date, no signs of intelligence have been found.

‘Oumuamua is an extremely dark object, absorbing 96% of the light that falls on its surface. It is coloured red, a hallmark of organic molecules, the building blocks of the biological molecules that allow life to function. Cigar-shaped, it is extremely elongated and roughly 400 metres long. This slowly spinning skyscraper-shaped object has a greyish-red surface crust and potentially ice in its heart.

The deep surface layer is made of carbon-rich gunk baked in interstellar radiation during its cosmic travels. This upper layer was formed when organic ices such as frozen carbon dioxide, methane and methanol were battered by the intense radiation that exists between the stars. The outer crust may have formed on the body when comet ices and comet dust grains were baked with high energy particles for millions or even billions of years. This process is what could have produced ‘Oumuamua’s tumbling motion, colour and unusual shape.

It is thought that ‘Oumuamua is an active asteroid, the remnants of a larger body that was torn apart by its parent star and then ejected into interstellar space. Indeed most planetary bodies consist of numerous pieces of rock that have coalesced under the influence of gravity. These can be imagined as sandcastles floating in space. With objects such as ‘Oumuamua passing through “habitable zones”, such as our own solar system, they may even carry with them seeds of life.

Perhaps ‘Oumuamua can be read as a kind of ur-sculpture, an object that has been crafted over millions of years with comet ices and dust, baked by cosmic radiation like a vase within a kiln. Made via processes of layering, melting, coalescing, colouring, tumbling, moving and travelling, it seems fitting to consider ‘Oumuamua in the context of an exhibition of artworks that are the result of material driven processes of making. Imaginatively bringing an interstellar object together with these artworks creates a collision that is capricious, but one that is also lively.

[attribution here – exhibition text]

References

“Do Scientists really think ‘Oumuamua is an alien spaceship?”The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/science/shortcuts/2018/nov/07/oumuamua-alien-spaceship-scientists-harvard-professors (Accessed 20 October 2020)

Stuart Clark, “Mysterious object confirmed to be from another solar system” The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/science/across-the-universe/2017/nov/20/interstellar-object-confirmed-to-be-from-another-solar-system (Accessed 20 Oct 2020)

Nicola Davis, “Interstellar object ‘Oumuamua believed to be ‘active asteroid” The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/science/2020/apr/13/interstellar-object-oumuamua-believed-to-be-active-asteroid(Accessed 20 October 2020)

Ian Sample, “Interstellar object ‘Oumuamua covered in ‘thick crust of carbon-rich gunk” The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/dec/18/interstellar-object-oumuamua-covered-in-thick-crust-of-carbon-rich-gunk (Accessed 20 October 2020)

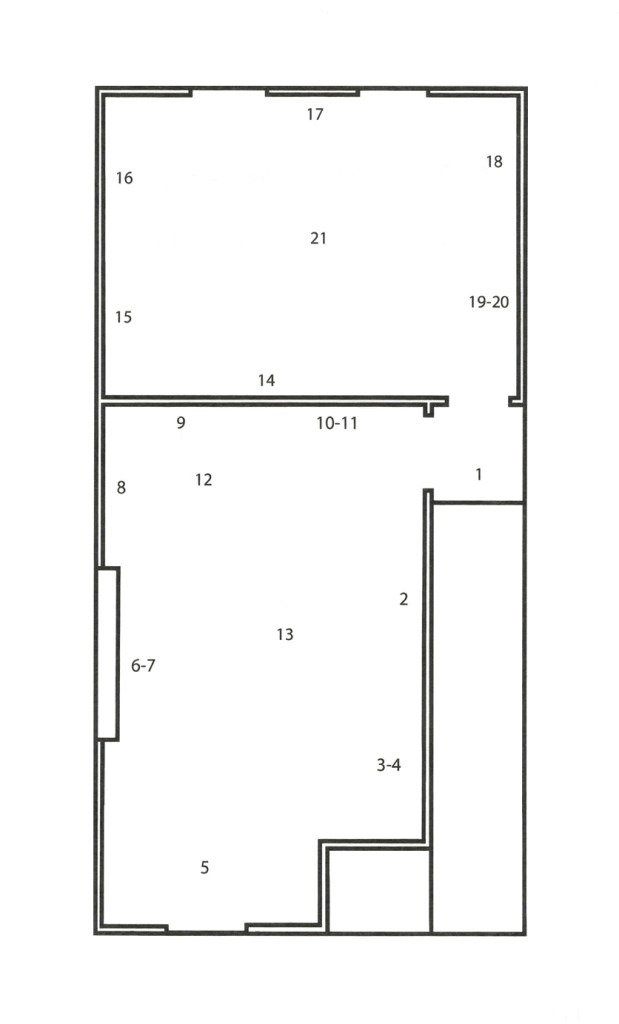

1 Celine Frampton, 3152294-1930 with ć Enilec variant2, 2020, Digital video, 4’ 15”

2 Wendy Lawson, To Piece – arm span 1760mm, 2020, Tea-stained canvas and glue

3-4 Samantha Cheng, green outdoor, large water, and water nature, boat mountain, 2020, Digital photographs

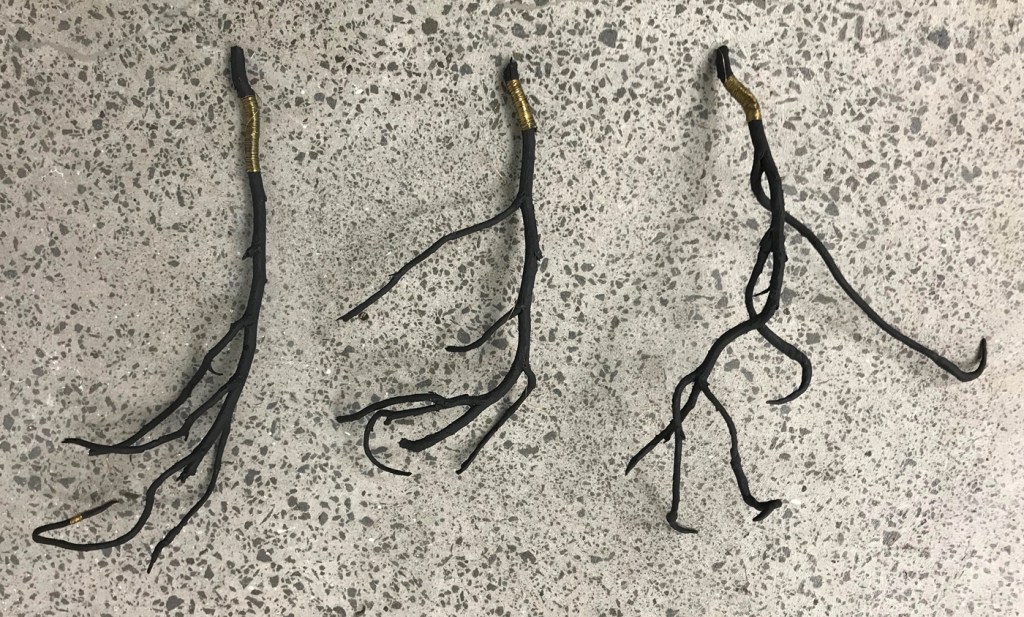

5 Abbie Read, An unsolicited acculturation, 2020, Charred non-native timbers, colonial pedestal, domestic ware, root systems, antique gold thread, hardboard canvas, paint, pencil, epoxy resin, screws

6-7 Matt Ellwood, Laurent/Vuitton #1 (Arnault/Pinault series), and Nathan on Guston, 2018, Charcoal on board

8 Amy Unkovich, Boldini’s Line, Four composite Modern Multi Panels, 2018, Concrete, pigments, salvage marble & granite, mild steel

9 Brunelle Dias, Lockdown studies, 2020, Watercolour on paper

10-11 Glen Snow, Loop-Hole, 2019, Wood, fabric (underwear leg band) and acrylic and A Kind of Excellent Dumb Discourse, 2015-2016, Wood, Builder’s Fill and acrylic

12 Dane Mitchell, A year of sleep, 2013, Rheum, glass, string

13 Tanya Martusheff, Untitled – (Pink Fascicle), 2019, Plastic hose, soap, cough syrup, zip ties, steel fixtures

14 Claudia Dunes, Compost Relief, 2020, High Impact polystyrene, vegetal components

15 Giulio Laura as OpenCo, Material Cost, 2019, Bought casting plaster on traded paint, found pastel and graphite, scrap canvas, and rescued vinyl

16 Dan Arps, Barrier Condition, 2020, Polyurethane and acrylic paint

17 Gitanjali Bhatt, rockroller, 2020, Found mechanical object camera apparatus, rolled through rock pools with an iPhone attached, at Hatfields beach, 5’ 25”

18 Louise Keen, Untitled (one for the movement), 2020, Bricolage, recycled clothing, tape, cotton thread, card on fabric

19-20 Stella Corkery, No Title and No Title, 2020, Oil on canvas

21 Fiona Cable, zam-zody, 2020, Raw alpaca & gotland fleece, merino, silk